World's Biggest Iceberg Is on a Collision Course With a Remote Penguin Sanctuary

The world's biggest iceberg is on a collision course with an overseas South Atlantic island that's home to thousands of penguins and seals, and will impede their ability to collect food, scientists told AFP Wednesday.

Icebergs naturally break removed from Antarctica into the ocean, but temperature change has accelerated the method - during this case, with potentially devastating consequences for abundant wildlife within the British Overseas Territory of South Georgia.

Shaped sort of a closed hand with a pointing finger, the iceberg called A68a split off in 2017 from Larsen ice on the western peninsula, which has warmed faster than the other a part of Earth's southernmost continent.

At its current rate of travel, it'll take the large cube - which is several times the world of the national capital - 20 to 30 days to run aground into the island's shallow waters.

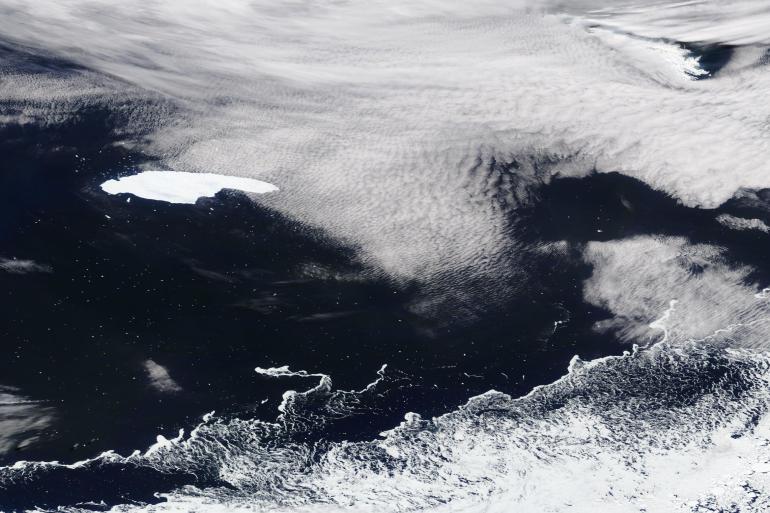

A NASA photo showing the iceberg A68a drifting in the South Atlantic between Antarctica and South Georgia (NASA/ESA)

A NASA photo showing the iceberg A68a drifting in the South Atlantic between Antarctica and South Georgia (NASA/ESA)

A68a is 160 kilometres (93 miles) long and 48 kilometres (30 miles) across at its widest point, but the iceberg is a smaller amount than 200 metres deep, which implies it could park dangerously near the island.

"We put the percentages of collision at 50/50," Andrew Fleming from Brits Antarctic Survey told AFP.

Many thousands of King penguins - a species with a bright splash of yellow on their heads - continue to exist the island, alongside Macaroni, Chinstrap and Gentoo penguins.

Seals also populate South Georgia, as do wandering albatrosses, the most important bird species that may fly.

If the iceberg runs aground next to South Georgia, foraging routes might be blocked, hampering the flexibility of penguin parents to feed their young, and thus threatening the survival of seal pups and penguin chicks.

Release of stored carbon

"Global numbers of penguins and seals would visit an oversized margin," Geraint Tarling, also from land Antarctic Survey, told AFP in an interview.

The incoming iceberg would also crush organisms and their seafloor ecosystem, which might need decades or centuries to recover.

(Martin Wettstein/Unsplash)

(Martin Wettstein/Unsplash)

Carbon stored by these organisms would be released into the ocean and atmosphere, adding to carbon emissions caused by an act, the researchers said.

As A68a drifted with currents across the Atlantic Ocean, the iceberg did an excellent job of distributing microscopic edibles for the ocean's tiniest creatures, said Tarling.

"Over many years, this iceberg has accumulated plenty of nutrients and mud, and that they are setting out to leach out and fertilise the oceans."

Up to a kilometre thick, icebergs are the solid-ice extension of land-bound glaciers. They naturally break faraway from ice shelves as snow-laden glaciers push toward the ocean.

But warming has increased the frequency of this process, referred to as calving.

"The amount of ice going from the centre of the continent out towards the sides is increasing in speed," Tarling said.

Up to the tip of the 20th century, the Larsen ice had been stable for over 10,000 years. In 1995, however, a large chunk broke off, followed by another in 2002.

This was followed by the breakup of the nearby Wilkins shelf ice in 2008 and 2009, and A68a in 2017.

Hydrofracturing - when water seeps into cracks at the surface, splitting the ice farther down - was almost certainly the most culprit in each case.

Comments

Post a Comment