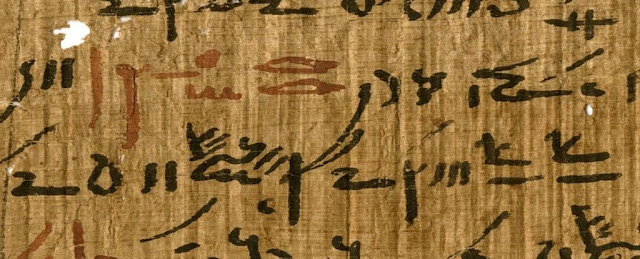

An analysis of 12 ancient papyrus fragments has revealed some surprising details about how the Egyptians mixed their red and black ink – findings which could give us lots more insight into how the earliest writers managed to urge their words down on the page.

We know that ancient Egyptians were using inks to put in writing a minimum of as far back as 3200 BCE. However, the samples studied during this case were dated to 100-200 CE and originally collected from the famous Tebtunis temple library – the sole large-scale institutional library is known to possess survived from the amount.

Using a kind of synchrotron radiation techniques, including the utilization of high-powered X-rays to analyse microscopic samples, the researchers revealed the fundamental, molecular, and structural composition of the inks in unprecedented detail.

"By applying the 21st century, state-of-the-art technology to reveal the hidden secrets of ancient ink technology, we are contributing to the disclosing of the origin of writing practices," says physicist Marine Cotte from the EU Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in France.

The red inks, typically wont to highlight headings, instructions, or keywords, were presumably coloured by the natural pigment ochre, the researchers say – traces of iron, aluminium, and hematite point to the present being the case.

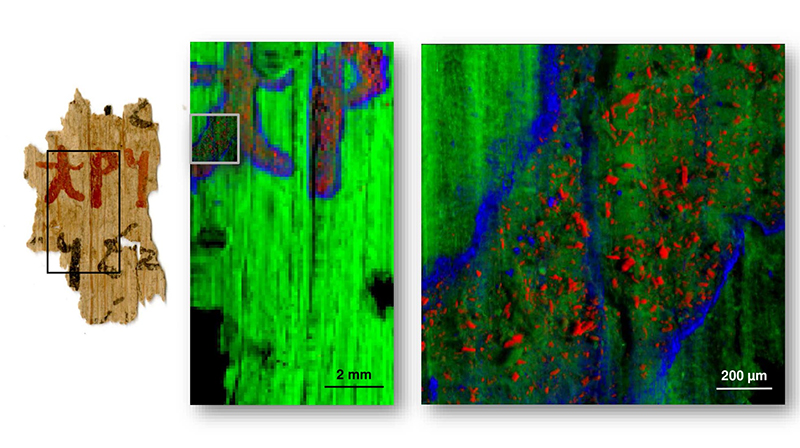

More intriguing was the invention of lead-based compounds in both the black and therefore the red inks, with none of the normal lead-based pigments used for colouring. this implies the lead was added for technical purposes.

"Lead-based driers prevent the binder from spreading an excessive amount of, when ink or paint is applied on the surface of paper or papyrus," the team writes in their study.

"Indeed, within the present case, lead forms an invisible halo surrounding the ochre particles."

As well as explaining how the traditional Egyptians kept their papyrus smudge-free, it also suggests some pretty specialised ink manufacturing techniques. It's likely that the temple priests who wrote using this ink weren't those who were originally mixing it.

"The indisputable fact that the lead wasn't added as a pigment but as a drier infers that the ink had quite a complex recipe and will not be made by just anyone," says Egyptologist Thomas Christiansen, from the University of Copenhagen in Denmark.

"We hypothesise that there have been workshops specialised in preparing inks."

X-ray fluorescence maps showing iron (red) and lead (blue) in the red ink. (The Papyrus Carlsberg Collection/ESRF)

X-ray fluorescence maps showing iron (red) and lead (blue) in the red ink. (The Papyrus Carlsberg Collection/ESRF)

Interestingly enough, the preparation of amount of money inside a workshop has also been mentioned during a Greek document dated to the third century CE, backing up the thought of specialized ink mixing in Egypt and across the Mediterranean.

This technique of using lead as a desiccant was also adopted in 15th century Europe as work of art began to seem – but it might seem that the traditional Egyptians discovered the trick a minimum of 1,400 years earlier.

The researchers are planning more tests and different forms of analysis, but what they've found thus far is already fascinating – another example of how modern-day scientific instruments can unlock even more secrets from the past, even right down to coloured ink.

"The advanced synchrotron-based microanalyses have provided us with invaluable knowledge of the preparation and composition of red and black inks in ancient Egypt and Rome 2,000 years ago," says Christiansen.

No comments:

Post a Comment