Solar Winds Hitting Earth Are Hotter Than They Should Be, And We May Finally Know Why

Our planet is continually bathed within the winds coming off the blistering sphere at the center of our scheme. But while the Sun itself is so ridiculously hot, once the solar winds reach Earth, they're hotter than they must be - and that we might finally know why.

We know that particles making up the plasma of the Sun's heliosphere cool as they unfolded. the matter is that they appear to require their sweet time doing so, dropping in temperature far slower than models predict.

"People are studying the solar radiation since its discovery in 1959, but there are many important properties of this plasma which are still not well understood," says physicist Stas Boldyrev from the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

"Initially, researchers thought the solar radiation needs to calm down very rapidly because it expands from the Sun, but satellite measurements show that because it reaches the planet, its temperature is 10 times larger than expected."

The research team used laboratory equipment to review moving plasma, and now think the solution to the matter lies in a very trapped sea of electrons that just can't seem to flee the Sun's grip.

The expansion process itself has long been assumed to be subject to adiabatic laws, a term that simply means energy isn't added or off from a system. This keeps the numbers nice and easy, but assumes there aren't places where energy slips in or out of the flow of particles.

Unfortunately, an electron's journey is anything but simple, shoved around at the mercy of vast magnetic fields sort of a roller coaster from Hell. This chaos leaves many opportunities for warmth to be passed back and forth.

Just to complicate matters further, because of its tiny mass, electrons get an honest advantage over heavier ions as they shoot forth from the Sun's atmosphere, leaving a largely positive cloud of particles in their wake.

Eventually, the growing attraction between the 2 opposing charges takes over the inertia of these flying electrons, pulling them back to the start where magnetic fields another time play havoc with their paths.

"Such returning electrons are reflected so they stream aloof from the Sun, but again they can't escape thanks to the attractive electric force of the Sun," says Boldyrev.

"So, their destiny is to make a comeback and forth, creating an oversized population of so-called trapped electrons."

Boldyrev and his crew recognized the same game of electron ping-pong playing enter their own laboratory, inside an apparatus commonly wont to study plasma called a mirror machine.

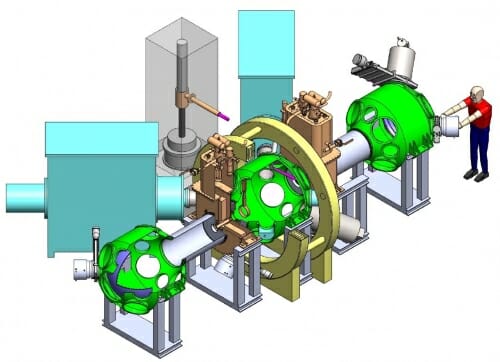

Diagram of a mirror machine

A linear fusion reactor, or 'mirror machine'. (Cary Forest)

A linear fusion reactor, or 'mirror machine'. (Cary Forest)

Mirror machines don't actually contain any mirrors. At least, not the familiar shiny kind. Also called magnetic mirrors or magnetic traps, these linear fusion devices are little quite long tubes with a bottle-neck at either end.

Their reflective nature is formed as streams of plasma passing through the bottle pinch in at either end, altering the encircling magnetic fields in such a way that particles within the stream reflect back inside again.

"But some particles can escape, and after they do, they stream along expanding field lines outside the bottle," Boldyrev says.

"Because the physicists want to stay this plasma very popular, they need to work out how the temperature of the electrons that escape the bottle declines outside this opening."

Or if you're Boldyrev and his team, those leaking electrons will be studied to higher understand what's happening with our very own solar radiation.

He and his colleagues suggest the population of trapped electrons that yo-yo back and forth play a serious role within the way electrons distributes their energy, changing the standard distributions of particle velocities and temperatures in predictable ways.

"It seems that our results agree o.k. with measurements of the temperature profile of the solar radiation and that they may explain why the electron temperature declines with space so slowly," says Boldyrev.

Finding such a decent match between the mirror machine's figures and what we see in space suggests there may be other solar phenomena worth studying this fashion.

Comments

Post a Comment