Even Vampire Bats Socially Distance Themselves When They Feel Sick

Bats have long endured a foul reputation, even before COVID-19 emerged. These highly mobile creatures that sleep in clustered colonies are well-known reservoirs of viruses, including coronaviruses, that, as we have seen, can spill over into humans.

But these innocent animals are unfairly maligned. they're important pollinators and pest controllers. And when bats are feeling sick, new research shows they naturally display their own type of social distancing behaviours, the same as the measures we've had to adapt to slow the spread of COVID-19.

The study had scientists tagging a bunch of untamed vampire bats from a colony in Lamanai, Belize, and tracking their social encounters every few seconds over a pair of days. after they injected the bats with a substance that triggered their immune systems, the 'sick' bats clearly changed their behaviour and have become less social.

"In the wild, [we observed] vampire bats – which are highly social animals – keep their distance when they're sick or living with sick groupmates," said Simon Ripperger, a bat researcher from The Ohio State University.

"And it will be expected that they reduce the spread of disease as a result."

Previous work from this group of researchers had shown that, in captivity, sick bats sleep more, move less, spend less time grooming other bats, and make fewer social calls (which usually attract their mates). The researchers call this 'sickness behaviour'.

"We really wanted to determine whether these behavioural changes also occur during a natural setting where the bats are within their natural social and physical environment," Ripperger told ScienceAlert.

Collecting data on social interactions between bats would even be useful if researchers want to predict how sickness behaviour can reduce the spread of disease in these animals, the identical way social distancing does in humans.

So the researchers analysed data from a briefly captured group of 31 common vampire bats (Desmodus rotundus), which are native to the geographical area, from a colony roosting inside a hollow tree.

Sixteen randomly selected female bats were injected with a substance to activate their system, which made them feel sick for some hours but didn't cause any real disease. Another 15 bats got a trial of salty water as a placebo.

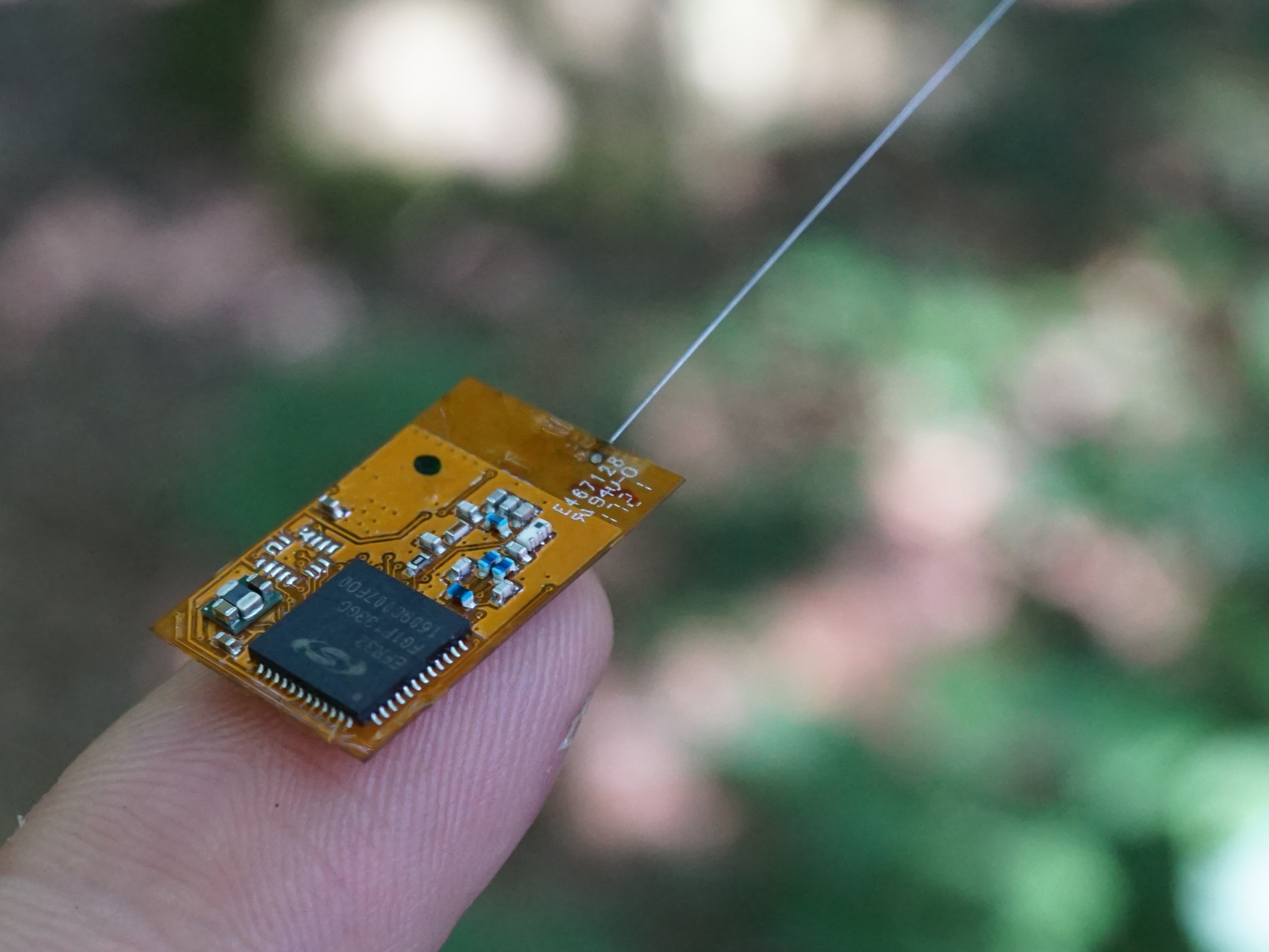

Before the 'sick' and healthy bats were returned to their roost, they also had tiny sensors, each weighing but a penny, glued to their furry little backs.

"The sensors gave us the chance to automatically track the behaviour of a complete grouping, instead of focal sample individuals at a time, what one usually does during a lab setting," Ripperger said. "That was an excellent success."

The custom sensors, designed by Ripperger and his colleagues, work by broadcasting a symbol every 2 seconds that 'wakes up' any neighbouring sensors (attached to a bat) within 5 to 10 metres.

Every time this happened within the three days after the bats were captured and released, the sensors logged an encounter. From the strength and duration of the pairwise signal, the scientists could tell when two bats came into close contact with each other, and for the way long.

"We focused on three measures of the sick bats' behaviours: what number other bats they encountered, what quantity total time they spent with others, and the way well-connected they were to the full social network," said behavioural ecologist Gerald Carter from The Ohio State University.

The network analysis shows that 'sick' bats were indeed less connected to their healthy, social roost mates.

In the first six-hour window after treatment, a 'sick' bat had on the average four fewer encounters than an impact bat, and 'sick' bats spent less time (25 minutes less) interacting with each partner.

As expected, 48 hours later, once the treatment had worn off and also the 'sick' bats were feeling better, they mostly resumed their normal social behaviours.

"It was amazing that the effect was so clearly visible," Ripperger told ScienceAlert.

"Even without a sophisticated statistical analysis you directly saw what's happening simply from gazing the social networks."

It should be noted that because the researchers didn't infect the vampire bats with a true virus or bacteria, they didn't measure the spread of an actual disease during a bat colony, which could influence bat behaviour in other ways.

"It is vital to recollect that changes in behaviour also depend upon the pathogen," Carter said. "Some real diseases might make interactions more likely, not less, or they could cause sick bats being avoided."

The study also only checked out a little group of bats within one roost.

Tracking how bats move and interact between colonies are a greater challenge, especially as scientists are just discovering the massive distances that bats travel – even thousands of kilometres every year – between roosts.

Comments

Post a Comment